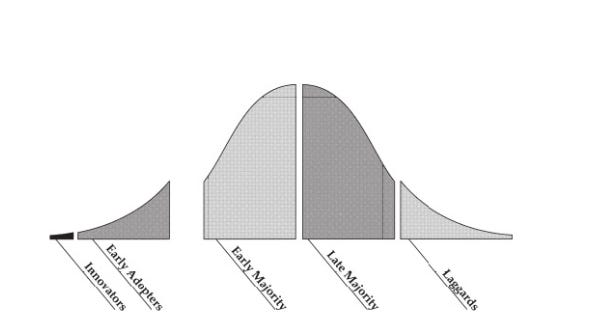

How a Technology Adoption Cycle Looks like

What the company staff interpreted as a ramp in sales leading smoothly “up the curve” was in fact an initial blip— what we will be calling the early market— and not the first indications of an emerging mainstream market.

What is a Market

Market , when it is defined in this sense, ceases to be a single, isolable object of action—it no longer refers to any single entity that can be acted on—and cannot, therefore, be the focus of marketing.

the burden of definition onto market, which we will define, forthe purposes of high tech, as:

a set of actual or potential customers

for a given set of products or services

who have a common set of needs or wants, and

who reference each other when making a buying decision.

About Innovators

They are the ones who first appreciate the architecture of your product and why it therefore has a competitive advantage over the current crop of products established in the marketplace. They are the ones who will spend hours trying to get products to work that, in all conscience, never should have been shipped in the first place. They will forgive ghastly documentation, horrendously slow performance, ludicrous omissions in functionality, and bizarrely obtuse methods of invoking some needed function—all in the name of moving technology forward. They make great critics because they truly care.

First, and most crucially, they want the truth, and without any tricks. Second, wherever possible, whenever they have a technical problem, they want access to the most technically knowledgeable person to answer it. Often this may not be sound from a management point of view, and you will have to deny or restrict such access, but you should never forget that it is wanted. Third, they want to be first to get the new stuff. By working with them under nondisclosure—a commitment to which they typically adhere scrupulously—you can get great feedback early in the design cycle and begin building a supporter who will influence buyers not only in his own company but elsewhere in the marketplace as well. Finally, they want everything cheap.

About Early Adopters

As a class, visionaries tend to be recent entrants to the executive ranks, highly motivated, and driven by a “dream.” The core of the dream is a business goal, not a technology goal, and it involves taking a quantum leap forward in how business is conducted in their industry or by their customers. It also involves a high degree of personal recognition and reward. Understand their dream, and you will understand how to market to them.

As a buying group, visionaries are easy to sell but very hard to please. This is because they are buying a dream that, to some degree, will always be a dream. The “incarnation” of this dream will require the melding of numerous technologies, many of which will be immature or even nonexistent at the beginning of the project. The odds against everything falling into place without a hitch are astronomical. Nonetheless, both the buyer and the seller can build successfully on two key principles.

The other key quality of visionaries is that they are in a hurry. They see the future in terms of windows of opportunity, and they see those windows closing. As a result, they tend to exert deadline pressures—the carrot of a big payment or the stick of a penalty clause—to drive the project faster. This plays into the classic weaknesses of entrepreneurs—lust after the big score and overconfidence in their ability to execute within any given time frame.

The goal should be to package each of the phases such that each phase:

is accomplishable by mere mortals working in earth time

provides the vendor with a marketable product

provides the customer with a concrete return on

investment that can be celebrated as a major step forward.

About Early Majority (Pragmatists)

Pragmatists tend to be “vertically” oriented, meaning that they communicate more with others like themselves within their own industry than do technology enthusiasts and early adopters, who are more likely to communicate “horizontally” across industry boundaries in search of kindred spirits. This means it is very tough to break into a new industry selling to pragmatists. References and relationships are very important to these people, and there is a kind of catch-22 operating: Pragmatists won’t buy from you until you are established, yet you can’t get established until they buy from you. Obviously, this works to the disadvantage of start-ups and, conversely, to the great advantage of companies with established track records. On the other hand, once a start-up has earned its spurs with the pragmatist buyers within a given vertical market, they tend to be very loyal to it, and even go out of their way to help it succeed.

Pragmatists want to buy from proven market leaders because they know that third parties will design supporting products around a market-leading product.

Pragmatists are reasonably price-sensitive. They are willing to pay a modest premium for top quality or special services, but in the absence of any special differentiation, they want the best deal. That’s because, having typically made a career commitment to their job and/or their company, they get measured year in and year out on what their operation has spent versus what it has returned to the corporation.

You need to show up at the industry- specific conferences and trade shows they attend. You need to be mentioned in articles that run in the newsletters and blogs they read. You need to be installed in other companies in their industry. You need to have developed applications for your product that are specific to their industry. You need to have partnerships and alliances with the other vendors who serve their industry. You need to have earned a reputation for quality and service. In short, you need to make yourself over into the obvious supplier of choice.

About Late Majority

Conservatives like to buy pre-assembled packages, with everything bundled, at a heavily discounted price. The last thing they want to hear is that the software they just bought doesn’t support the home network they have installed. They want high-tech products to be like refrigerators—you open the door, the light comes on automatically, your food stays cold, and you don’t have to think about it. The products they understand best are those dedicated to a single function— music, video, email, games. The notion that a single device could do all four of these functions does not excite them— instead, it is something they find vaguely nauseating.

Finding your way into the mainstream

You must get into a mainstream market segment soon, establishing long-term relationships with pragmatist buyers, for only through these can you control your own destiny.

To enter the mainstream market is an act of aggression. The companies who have already established relationships with your target customer will resent your intrusion and do everything they can to shut you out. The customers themselves will be suspicious of you as a new and untried player in their marketplace. No one wants your presence. You are an invader.

The sole goal of the company during this stage of market development must be to secure a beachhead in a mainstream market—that is, to create a pragmatist customer base that is reference-able, people who can, in turn, gain us access to other mainstream prospects. To capture this reference base, we must ensure that our first set of customers completely satisfy their buying objectives.

To be the leader in any given market, you need the largest market share—typically over 50 percent of the new sales at the beginning of a market, although it may end up to be as little as 30–35 percent later on. So, take the sales you expect to generate over any given time period—say the next two years—double that number, and that’s the size of market you can expect to dominate. Actually, to be precise, that is the maximum size of market, because the calculation assumes that all your sales came from a single market segment. So, if we want market leadership early on—and we do, since we know pragmatists tend to buy from market leaders, and our number- one marketing goal is to achieve a pragmatist installed base that can be referenced—the only right strategy is to take a “big fish, small pond” approach.

Segment. Segment. Segment. One of the other benefits of this approach is that it leads directly to you “owning” a market. That is, you get installed by the pragmatists as the leader, and from then on, they conspire to help keep you there. This means that there are significant barriers to entry for any competitors, regardless of their size or the added features they have in their product. Mainstream customers will, to be sure, complain about your lack of features and insist you upgrade to meet the competition. But, in truth, mainstream customers like to be “owned”—it simplifies their buying decisions, improves the quality and lowers the cost of whole product ownership, and provides security that the vendor is here to stay

How Macintosh got Mainstream

When the Macintosh first crossed the chasm back in the 1980s, the target niche was the graphics arts departments in Fortune 500 companies. This was not a particularly large target market, but it was one that was responsible for a broken, mission-critical process—providing presentations for executives and marketing professionals.

More important, however, having dominated this niche, the company was then able to leverage its win into adjacent departments within the corporation—first marketing, then sales. The marketing people found that if they made their own presentations, they could update them on the way to the trade shows, and the salespeople found that with a Mac they didn’t have to rely on the marketing people. At the same time, this beachhead in graphics arts also extended out into external markets that interfaced with the graphics arts people—creative agencies, advertising agencies, and eventually, publishers. All used the Macintosh to exchange a variety of graphic materials, and the result was a complete ecosystem standardized on the “nonstandard” platform.

How Pragmatist Adopt a New Product

Pragmatist customers rarely adopt any new technology en masse. Usually these innovations are taken up first by a single niche, one that has such pressing problems it goes ahead of the herd. The rest of the herd is delighted by this eventuality because it gets a free look at how well the technology plays out without having to take any immediate risk. The niche wins—presuming the beach head strategy is conducted correctly—by getting a state-of-the-art fix for its heretofore unsolvable problem. And the vendor wins because it gets certified by at least one segment of pragmatists that its offering is legitimately mainstream.

A key lesson to learn here is that you want to target a beachhead segment that is:

Big enough to matter

Small enough to win, and a

Good fit with your crown jewels.

From Idea to Implementation

select the point of attack, the place to cross, the beachhead, the head bowling pin. Then we will look at

what kind of offer it will take to secure that initial target market, and how we as a fledgling enterprise with limited resources can go about fielding such an offer.

we will look at the landscape, identifying the forces that seek to throw us off the beach and back into the chasm, and how we can position ourselves for success.

selling systems themselves, pricing and distribution, to help us pick the right approach to the market during this particularly vulnerable time.

The Market Development Strategy checklist

This list consists of a set of issues around which go-to-market plans are built, each of which incorporates a chasm-crossing factor, as follows:

Target customer

Compelling reason to buy

Whole product

Partners and allies

Distribution

Pricing

Competition

Positioning

Next target customer

Committing to the Point of Attack

Making the commitment to a niche market can be challenging, especially for entrepreneurs who are technology enthusiasts or visionaries, because they personally don’t have the pragmatist response and thus have trouble trusting in the market dynamics outlined in this book. This is a defining moment for them. The start-up company must either cross or die, but what value is life if to gain it one has to go against one’s best self? Not an easy question to answer.

The Target Market Selection Process

Develop a library of target customer scenarios. Draw from anyone in the company who would like to submit scenarios, but go out of your way to elicit input from people in customer-facing jobs. Keep adding to it until new additions are no more than minor variations on existing scenarios.

Appoint a subcommittee to make the target market selection. Keep it as small as possible but include on it anyone who could veto the outcome.

Number and publish the scenarios in typed form, one page per scenario. Accompanying the bundle, provide a spreadsheet with the rating factors assigned to columns and the scenarios assigned to rows. Break the rating factors into two subtotals, showstoppers first, then nice-to-haves.

Have each member of the subcommittee privately rate each scenario on the showstopper factors. Roll up individual ratings into a group rating. During this process discuss any major disagreements about scores. This typically surfaces different points of view on the same scenario and is critical not just to getting the opportunity correctly in focus but also in laying the groundwork for a future consensus that will stick.

Rank order the results and set aside scenarios that do not pass the first cut. This is typically about two-thirds of the submissions.

In a 400-degree oven, bake ... (Oops! Wrong book. Sorry.) Repeat the private rating and public ranking process on the remaining scenarios with the remaining selection factors. Winnow the scenario population down to, at most, a favored few.

Depending on outcome, proceed as follows:

Group agrees on beachhead segment. Go forward on that basis.

Group cannot decide among a final few. Give the assignment to one person to build a bowling pin model of market development, incorporating as many of the final few as is reasonable, and calling out a head pin. Attack the head pin.

No scenario survived. This does happen. In that case, do not attempt to cross the chasm. Also, do not try to grow. Continue to take early-market projects, keep burn rate as low as possible, and continue the search for a viable beachhead.

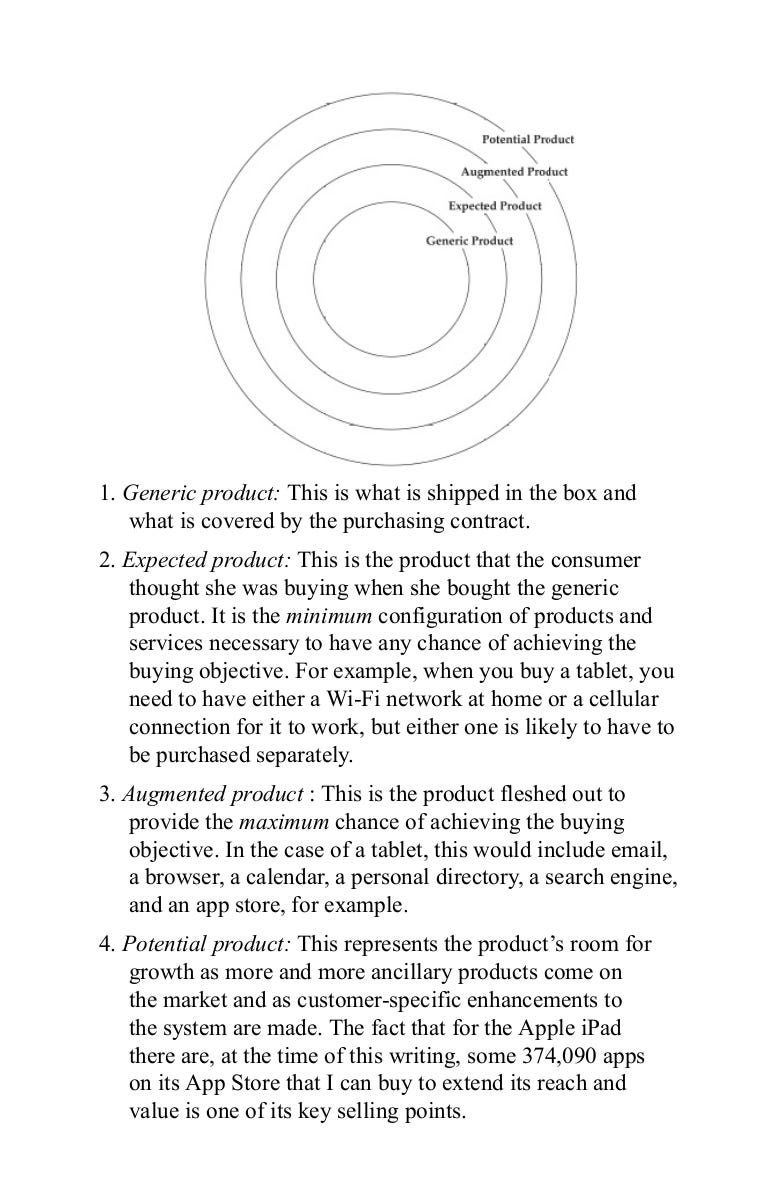

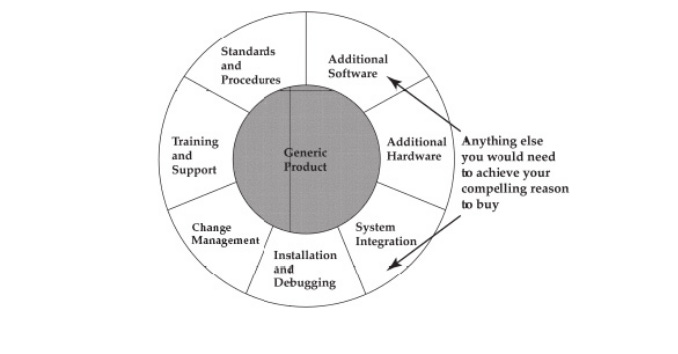

The whole product concept

For a given target customer and a given application, create a marketplace in which your product is the only reasonable buying proposition.

targeting markets that have a compelling reason to buy your product.

The next step is to ensure that you have a monopoly over fulfilling that reason to buy.

To secure that monopoly, you need to understand

what a whole product consists of

how to organize a marketplace to provide a whole product incorporating your company’s offering.

Visionaries, by contrast, take no pleasure in pulling together a whole product on their own, but they accept that, if they are going to be the first in their industry to implement the new system—and thereby gain a strategic advantage over their competitors—then they are going to have to take responsibility for creating the whole product under their own steam. The rise in interest in systems integration services is a direct response to increasing visionary interest in information systems as a source of strategic advantage. Systems integrators could just as easily be called whole product providers—that is their commitment to the customer.

In the simplified model there are only two categories: 1) what we ship and 2) whatever else the customers need in order to achieve their compelling reason to buy. The latter is the marketing promise made to win the sale. The contract does not require the company to deliver on this promise, but the customer relationship does. Failure to meet this promise in a business-to-business market has extremely serious consequences. As the bulk of purchases in this marketplace are highly reference oriented, such failure can only create negative word of mouth, causing sales productivity to drop dramatically.

Tips on whole product management

Review the whole product from each participant’s point of view. Make sure each vendor wins, and that no vendor gets an unfair share of the pie. Inequities here, particularly when they favor you, will instantly defeat the whole product effort—companies are naturally suspicious of each other anyway, and given any encouragement, will interpret your entire scheme as a rip-off.

Develop the whole product relationships slowly, working from existing instances of cooperation toward a more formalized program. Do not try to institutionalize cooperation in advance of credible examples that everyone can benefit from it—not the least of whom should be the customers. Also, do not recruit directly competing partners to serve the same need in the same segment—this will only discourage them from making a full commitment to your program.

With large partners, try to work from the bottom up; with small ones, from the top down. The goal in either case is to work as close as possible to where decisions that affect the customer actually get made.

Once formalized relationships are in place, use them as openings for communication only. Do not count on them to drive cooperation. Partnerships ultimately work only when specific individuals from the different companies involved choose to trust each other.

If you are working with very large partners, focus your energy on establishing relationships at the district sales office level and watch out for wasting time and effort with large corporate staffs. Conversely, if you are working with small partners, be sensitive to their limited resources and do everything you can to leverage your company to work to their advantage.

Finally, do not be surprised to discover that the most difficult partner to manage is your own company. If the partnership really is equitable, you can count on someone inside your company insisting on taking a bigger share of the benefit pie. In fighting back, look to your customers to be your truest and most powerful allies.

Positioning

Creating the competition, more than anything else, represents a watershed moment in positioning. Positioning is the most discussed and least understood component of high-tech marketing. You can keep yourself from making most positioning gaffes if you will simply remember the following principles:

Positioning, first and foremost, is a noun, not a verb. That is, it is best understood as an attribute associated with a company or a product, and not as the marketing contortions that people go through to set up that association.

Positioning is the single largest influence on the buying decision. It serves as a kind of buyers’ shorthand, shaping not only their final choice but even the way they evaluate alternatives leading up to that choice. In other words, evaluations are often simply rationalizations of pre-established positioning.

Positioning exists in people’s heads, not in your words. If you want to talk intelligently about positioning, you must frame a position in words that are likely to actually exist in other people’s heads, and not in words that come straight out of hot advertising copy.

People are highly conservative about entertaining changes in positioning. This is just another way of saying that people do not like you messing with the stuff that is inside their heads. In general, the most effective positioning strategies are the ones that demand the least amount of change.

Four primary psychographic types

Now, the nature of that best-buy space is a function of who is the target customer. Indeed, this space builds and expands cumulatively as the product passes through the Technology Adoption Life Cycle. There are four fundamental stages in this process, corresponding to the

Name it and frame it. Potential customers cannot buy what they cannot name, nor can they seek out the product unless they know what category to look under.

Who for and what for. Customers will not buy something until they know who is going to use it and for what purpose. This is the minimum extension to positioning needed to make the product easy to buy for the visionary.

Competition and differentiation . Customers cannot know what to expect or what to pay for a product until they can place it in some sort of comparative context. This is the minimum extension to positioning needed to make a product easy to buy for a pragmatist.

Financials and futures . Customers cannot be completely secure in buying a product until they know it comes from a vendor with staying power who will continue to invest in this product category. This is the final extension of positioning needed to make a product easy to buy for a conservative.

Positioning in 4 steps

The claim. The key here is to reduce the fundamental position statement—a claim of undisputable market leadership within a given target market segment.

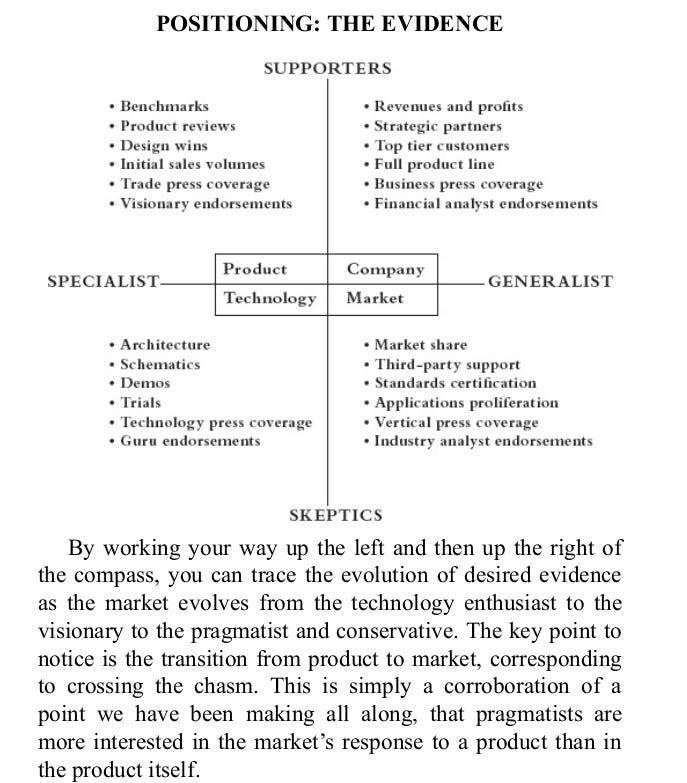

The evidence. The claim to undisputed leadership is meaningless if it can, in fact, be disputed. The key here is to present sufficient evidence as to make any such disputation unreasonable.

Communications. Armed with claim and evidence, the goal here is to identify and address the right audiences in the right sequence with the right versions of the message.

Feedback and adjustment. Just as football coaches have to make halftime adjustments to their game plans, so do marketers, once the positioning has been exposed to the competition. Competitors can be expected to poke holes in the initial effort, and the

These were the major fundamental concepts from this book

Thanks for reading. I am glad you took out time from your busy life to read this.